Article and Photos by MARGIE O’LOUGHLIN

When Michelle Howard, Clean City Coordinator for the City of Minneapolis was asked how graffiti started, she said, “I think when the first cave paintings were made.” Human beings are born with an instinct to make their mark, both figuratively and literally.

When Michelle Howard, Clean City Coordinator for the City of Minneapolis was asked how graffiti started, she said, “I think when the first cave paintings were made.” Human beings are born with an instinct to make their mark, both figuratively and literally.

Photo right: Jimmie Denson, Graffiti Removal Team for the city, tackled a control box in South Minneapolis for the umpteenth time. He said, “This tagger just keeps coming back over and over again.”

The graffiti we see around town came out of the Bronx, New York, in the late 1960’s. It’s the most visible element of Hip-Hop culture, the others being emceeing, DJ-ing and break dancing. Writers, as graffiti artists prefer to be called, started doing their art on subway trains almost fifty years ago.

The goal was, and is, to “get up,” to have one’s name or one’s art seen in as many places as possible. Once that’s done, writers try to out-do each other for style. The fact that making graffiti is an act of vandalism shoots it full of adrenaline, and the risk of arrest makes writers work really fast. Note that graffiti is only considered vandalism when no permission was given to create it….

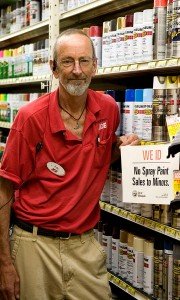

Photo left: Tom Buskirk, East Lake Frattalone Hardware, said, “We card anyone who appears to be a minor.” According to city ordinance #223.170, it’s illegal for a hardware store to sell spray paint to anyone under 18.

Photo left: Tom Buskirk, East Lake Frattalone Hardware, said, “We card anyone who appears to be a minor.” According to city ordinance #223.170, it’s illegal for a hardware store to sell spray paint to anyone under 18.

Whether or not you appreciate graffiti as an art form, it’s safe to say that no one wants to have their property “tagged.” Unwanted graffiti has a negative effect on a neighborhood and decreases property values. There are a few steps property owners can take to make their home or business less attractive to graffiti vandals.

In Longfellow and Nokomis, garages are the most likely target for graffiti. Taggers prefer a smooth, flat surface so planting shrubs or vines, creating a mural yourself, or having improved garage lighting will all act as deterrents. If you do create your own mural, there’s an etiquette among graffiti writers that’s almost always observed: they won’t paint over someone else’s art.

Fences that border on alleys are also prime targets. Choosing a style with board gaps or lattices is best.

What to do if your home or business has been tagged?

Persons whose property has been damaged are considered victims of a crime. The City of Minneapolis makes free, environmentally-friendly solvents available for pick-up at any fire station. The product, which is available in quarts, will clean up almost any spray paint.

Most property owners remove graffiti themselves. Howard said, “If washing with our solvent isn’t enough, the best solution is to paint the whole garage wall that’s been tagged. If you just paint over the tag itself, especially if your paint doesn’t quite match, the tagger will likely return and enjoy the ‘frame’ you’ve created.”

If a porous surface like stucco or brick has been tagged, using a power washer is the only option.

How to report graffiti?

If you see a graffiti crime in action, call 911. While the arrest rate for graffiti writers is extremely low (only about 1%, according to Howard), it is still a crime.

Call 311 if a property, including your own, has been tagged in your neighborhood. A work order will be sent out the next day, and a member of the Graffiti Removal Team will come and photograph the graffiti. From that time, the home or business owner will have one week to remove the tag—or the City will come and do it for them, and send them the bill.

Angela Breen, an administrative analyst with the City of Minneapolis, said, “The City has an annual budget of just under a million dollars for graffiti removal. Minneapolis has a stated zero tolerance for graffiti, so as fast as the writers are putting it up—the City is taking it down.”

On occasion, an extension can be granted to a property owner for hardship, but, according to Howard, “it doesn’t happen often.” Block Clubs and the Senior Linkage Line may be able to connect elderly neighbors to resources and help them get services.

The Graffiti Removal Team is especially busy during the warm months removing tags from public places. The optimal temperature for spray paint is between 55-90 degrees. The four-person team uses a soy-based product similar to what’s handed out at fire stations for flat surfaces and, for the really tough stuff, an industrial-strength solvent called (believe it or not) Elephant Snot.

“It’s not pretty, but it gets the job done,” explained Jimmie Denson, a six-plus year veteran of the team.

As Denson and co-worker Eric Tullki pulled up to a South Minneapolis control box covered with tags, they muttered, “So this guy’s coming around again.” Tullki added, “We see the same tags all over the place for a while, and then they move on.”

“Contrary to public perception, very little graffiti is thought to be gang-related,” said Howard. She estimated that in Minneapolis, the numbers are as low as 3%. The small amount of graffiti that is gang-related marks a territory, and can be used to recruit new members. But the vast majority is just about putting up one’s mark—maybe because the writer feels there’s no other way to be seen or heard.

Photo right: A full fledged, permission-given mural of aerosol art in South Minneapolis.

Photo right: A full fledged, permission-given mural of aerosol art in South Minneapolis.

By JoJo of Murals by Eros

A “tag” is considered the lowest level of our art, just the quick signature on a surface. Next up is a “throwie,” given that name because it’s a simplified, bubble style that’s thrown up on a wall real fast. Then there is a “piece,” which is short for masterpiece. These are the bright colorful, word and letter combinations of the artist’s name. A piece generally takes many hours and a lot of paint to complete. The very highest level is called a “burner,” and can only be executed by the most experienced and talented in the area.

In short, a throwie goes up over a tag. A piece can go over a throwie and a burner goes over everything.

If these so-called rules are violated, there can be consequences—like other writers going over the violator’s work. The person violating the rules also loses respect in the culture.

The culture typically polices itself.

Note: Jojo runs a program in South Minneapolis known as The G.A.M.E. (Graffiti Art Mentoring & Education)

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here