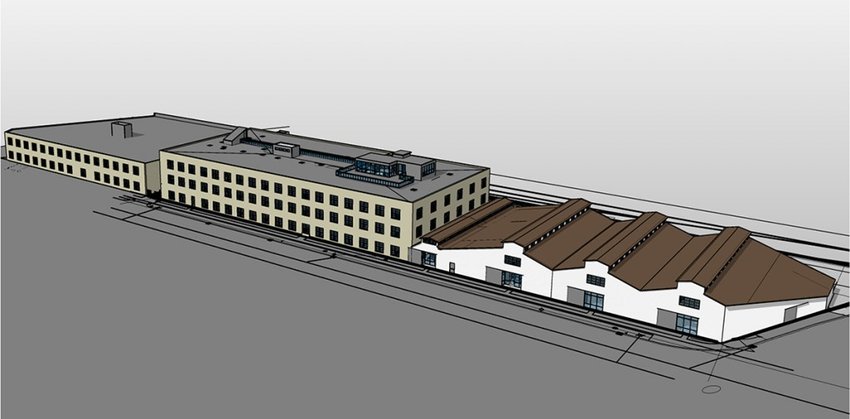

Millwork Lofts will be set apart by timber and beams used when the

Millwork Lofts will be set apart by timber and beams used when the buildings were constructed in the 1920s

By TESHA M. CHRISTENSEN

For nearly a century, the three connected buildings between 40th and 41st St. along Hiawatha Ave. have provided jobs.

Now the old factories and sheds are being transformed to provide another basic need: housing.

“That building doesn’t look like much right now, but when we’re done it will look pretty cool,” promised Nick Anderson, a developer with the Plymouth-based Dominium, Inc.

Millwork Lofts

Dominium’s interest in the site was sparked by its prime location along Hiawatha Ave., a few blocks south of a light rail station.

Because of its age, the project is eligible for historic cash credits, which were needed to make the project financially feasible, according to Anderson.

Photo right: The loft style apartments with high ceilings and polished concrete floors will prominently feature the timber posts and beams present in the old factory. (Photo submitted)

Photo right: The loft style apartments with high ceilings and polished concrete floors will prominently feature the timber posts and beams present in the old factory. (Photo submitted)

“More of this moderately-priced housing is needed desperately in Minneapolis,” remarked Anderson. One to two bedroom units in Millwork Lofts will rent for between $900 and $1,100.

In all, there will be 55 one-bedroom units, 22 two-bedroom units, and one three-bedroom.

The loft style apartments with high ceilings and polished concrete floors will prominently feature the timber posts and beams present in the old factory.

“The demand for this type of building is very strong,” stated Anderson.

A spacious community room will be located on level one of the shed, which will also be divided up to offer indoor parking and bike storage.

The original windows in the peaks of the shed will bring in light once more. Plus, the metal sheeting added in 1986 will be removed to let the historic white clapboard show.

The complex will have a fitness room and yoga studio.

A smaller community room and patio will sit on top of the three-story building.

Another unique component of the building is the planned geothermal heating and cooling system. The site affords enough space to bury coils in the parking lot behind the building, which will pull heat out in the winter and put heat back in the summer. A boiler connects to vents that will push the hot and cold air into apartments.

It’s rare to find such systems in the city because there often isn’t enough space, Anderson pointed out. Coils need to be located in an area where they can be accessed in case there is a problem. A building can’t be torn down, but a parking lot can be ripped up and redone easily.

“It’s a good system for this site because of the big parking lot behind the building,” said Anderson.

Construction begins in mid-July and will take roughly 12 months.

Past Dominium projects include the $125 million redevelopment of the once-neglected Schmidt Brewery in St. Paul into apartments for artists to live and work, and the $156 million conversion of the fabled Pillsbury A Mill complex of buildings into the 251-unit A Mill Artist Lofts.

Only remaining millwork in Hiawatha corridor

The project is also set apart by its historic nature.

Constructed in what was a successive building campaign from 1926 to 1928 on the undeveloped land between Hiawatha Ave. and the railroad, the Lake Street Sash and Door complex soon spanned a full city block, evidencing its success, while also extending the Hiawatha corridor further south.

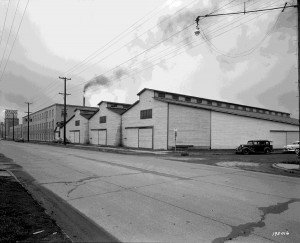

Photo left: The block-long Lake Street Sash and Door Company complex churned out sash, door, blind and other millwork items until it closed in 1964 due to a shrinking list of customers. The south two buildings will be transformed into loft-style apartments by the Plymouth-based Dominium. Work will begin in mid-July and finish next May. The metal sheeting on the large shed will be removed to reveal the old white clapboard siding underneath. Circa 1950. (Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

Photo left: The block-long Lake Street Sash and Door Company complex churned out sash, door, blind and other millwork items until it closed in 1964 due to a shrinking list of customers. The south two buildings will be transformed into loft-style apartments by the Plymouth-based Dominium. Work will begin in mid-July and finish next May. The metal sheeting on the large shed will be removed to reveal the old white clapboard siding underneath. Circa 1950. (Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

As the only remaining millwork in Hiawatha corridor today, the complex also stands as an intact representative of Minneapolis’ sash and door industry during the early-to-mid-20th century. It consisted of its factory, warehouse, and lumber shed, according to Jennifer F. Hembree of MacRostie Historic Advisors who put together the National Register Nomination for the Lake Street Sash and Door Company.

The lengthy process to designate the area a historic site began in January 2015 and didn’t conclude until July 2016.

The property is associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of local history.

More than any other city

Beginning in 1864, the Minnesota Central Railway Company began construction of a line linking Saint Anthony Falls with Fort Snelling. The rail line ran between and parallel to Minnehaha Ave. to the east, the first road built to connect Fort Snelling with downtown Minneapolis, and Hiawatha Ave. to the west, establishing a transportation corridor. In fact, Hiawatha Ave. was first called Fort Ave.

Photo right: Lake Street Sash and Door Company complex, view southeast toward the corner of 40th St. and Hiawatha Ave. (l to r) Warehouse, factory 2, and lumber shed, circa 1920s. (Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

Photo right: Lake Street Sash and Door Company complex, view southeast toward the corner of 40th St. and Hiawatha Ave. (l to r) Warehouse, factory 2, and lumber shed, circa 1920s. (Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

The construction of grain elevators between 3400 and 4100 Hiawatha, was followed by lumber and fuel yard businesses that were attracted to the area due to their need for large land parcels and rail spurs, according to the Hiawatha Grain Corridor Industry Historic District document on file at the Minnesota State Historic Preservation Office.

Wood product and millwork companies, such as Lake Street Sash and Door Company came next.

The Minneapolis millwork industry—plants that manufactured wood products such as blinds, sashes, doors, shingles, moldings, stairs and even cabinetry, grew out of the city’s booming lumber industry that began with the erection of the military’s sawmill at Saint Anthony Falls.

Photo left: Lake Street Sash and Door Company complex, view southeast toward the corner of 40th St. and Hiawatha Ave. (l to r) Warehouse, factory 2, and lumber shed, circa 1950. (Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

Photo left: Lake Street Sash and Door Company complex, view southeast toward the corner of 40th St. and Hiawatha Ave. (l to r) Warehouse, factory 2, and lumber shed, circa 1950. (Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society)

The availability of massive amounts of lumber, as well as the increased demand for finished wood products, resulted in Minneapolis becoming the leading producer of sashes, doors and other millwork in the country by 1910.

Isaac Atwater, in his “The History of the City of Minneapolis,” stated that in 1880-85, 20 factories, large and small were in operation. “Minneapolis had more machinery engaged in the manufacture of sash, door and blinds than any other city on the continent,” Atwater wrote.

The Lake Street Sash and Door Company was the first, and soon a significant and longstanding millwork industry player along the Hiawatha transportation corridor.

$300,000 factory ready in two weeks

Founded by Helmar Knudsen (1881-1970), the Lake Street Sash and Door Company was organized in 1916.

The company redeveloped the former Northwestern Fuel Yard property for its first factory at 3121-47 Hiawatha Ave.

Almost immediately, Lake Street Sash and Door experienced increasing sales and in late 1922, Knudsen petitioned the city council to construct a factory on the vacant lots between E. 40th and E. 41st streets, the railway and Hiawatha Ave., according to the National Register Nomination paperwork.

At the same time, the enclosed lumber shed was built, which helped shelter the lumber from the elements, while providing proper ventilation thanks to recent advancements in the design. The enclosed lumber shed gave Lake Street Sash and Door Company a leg up on its competition.

The Minneapolis Journal exclaimed on Oct. 2, 1926, “$300,000 Factory Ready in 2 Weeks.” The firm added 100 staff at its new location, while it maintained 75 employees at its first factory.

The firm continued to utilize Factory 1 until 1931 when E. E. Bach Millwork moved into its space.

During the Great Depression, the firm is credited as furnishing the door and millwork associated with the construction of the municipal hospital in Spencer, Iowa in 1938, as well as the millwork for the Reedsville post office in Wisconsin.

According to newspaper accounts, the 1950s were the firm’s “peak years,” when it averaged $3 million annually.

The firm’s 1952 catalog indicates a variety of sash, door, blind and other millwork items including entrance frames with pilasters and trim, some paneled entrance door styles, double-hung window units, inclusive of their balances, overhead garage doors, louvers, and decorative window blinds.

Despite the success in the 1950s, Lake Street Sash and Door Company closed its doors in 1964 due to a shrinking list of regular customers, especially among small contractors, as reported in the Apr. 17, 1964 Minneapolis Star Tribune.

A variety of other businesses have used the buildings over the past few decades, most recently American Carton Polybag Company.

The original warehouse facility and company office at the northernmost part of the block is still being used by IAC International and is not part of this project.

Two sash and door factories in Minneapolis have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Both are located within the Saint Anthony Falls Historic District. The Island Sash and Door Company (1893) only survived sixteen years (although the single building is extant today as a hotel), and the Roman Alexander Sash and Door (1908) factory building was razed to establish a park.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here