A view of the Atkinson Mill today—still standing for almost 100 years, 3745 Hiawatha Ave. [/caption]

A view of the Atkinson Mill today—still standing for almost 100 years, 3745 Hiawatha Ave. [/caption] By LINDSAY GROME

Mill City—it’s the place we all call home, but long gone are the days of flour sacking in the Twin Cities. Once declared the mill capital of the nation, Minneapolis today remains home to only two working flour mills, and they happen to be in our own backyard.

“We produce about 75 percent white flour and 25 percent animal feed,” said Charles Hatch, General Operations Manager for Atkinson Mill and Nokomis Mill, located at 3745 and 3501 Hiawatha Ave, respectively. He’s been working at the mills for 32 years.

“Both plants were built around 1914 to 1916,” said Hatch. “So, yeah, we’re working in some old buildings.”

For about 100 years, these plants have been turning wheat into flour to make the breads, pastries, tortillas and pizza crusts we all know and love.

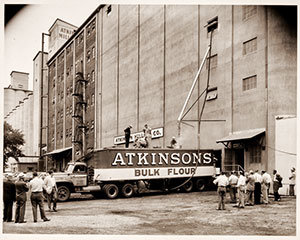

Men load a truck at the Atkinson Mill, dated approximately 1950. (Photo provided by the Minnesota Historical Society)

Men load a truck at the Atkinson Mill, dated approximately 1950. (Photo provided by the Minnesota Historical Society)According to the Minnesota Historical Society, in 1880 Minneapolis was home to 25 mills, with the city claiming the title of the largest flour producer in the nation. It was a title it held for 50 years. Today, Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) owns both of these last mills in the city that are still producing flour.

According to Grain and Milling Annual, the state of Minnesota is still home to eight mills, producing roughly 11.1 million pounds of flour a year—second only to the state of California. ADM is the second largest miller in the United Sates with 25 mills. The Minneapolis mills on Hiawatha Ave. produce roughly two million pounds of flour a day.

The location on Hiawatha, once a highly industrious area hosting a slew of factories and mills, has proven to be ideal for success. Sitting right on the Minnesota Commercial Railway, the plants rely on railcars from the west and north, including North Dakota, South Dakota and Canada to bring in the wheat and to ship out the final product. About 200,000 pounds of flour per railcar is shipped to the east and south, sometimes as far away as West Virginia.

While the mode of transportation hasn’t changed in some instances, the milling process has come a long way. Hatch says the same building can now produce roughly three times more flour than when they first milled there in the early 1900s.

“Some parts of the process have been changed, but the basic properties are the same, said Hatch. “Most of the equipment has been replaced over the years—bulk really changed the footprint.”

Before the 1950s, sacking flour was the sole distribution method of the powdery substance. That is, until bulk delivery of flour was pioneered by a plant engineer at the Atkinson Mill. Based on this method, now tanker trucks are loaded to capacity at 50,000 pounds to be driven to commercial bakeries nationwide, including many local and regional favorites.

The delivery method of flour isn’t the only thing that’s changed. Hatch says safety standards have had a great impact as well. For instance, dust, a highly combustible output of the milling process that can cause explosions and serious safety hazards to the millers, is now controlled by dust control filters. That dust is now used to create a byproduct used in animal feed, which is then sold to other companies.

Hatch couldn’t reveal the exact number of employees at the two remaining mills, but he said the company employs a lot of people from Minneapolis and surrounding suburbs, allowing access to a good workforce locally for manufacturing jobs.

The Atkinson and Nokomis Mills sift and purify wheat in six stages until it turns into the white flour that is then turned into bread and other pastries at commercial bakeries. (Photo provided by Atkinson Mill) [/caption]

The Atkinson and Nokomis Mills sift and purify wheat in six stages until it turns into the white flour that is then turned into bread and other pastries at commercial bakeries. (Photo provided by Atkinson Mill) [/caption] “There was one employee who lived just blocks away and he rode his bike to work every day for 30 years,” said Hatch, “We operate very efficiently, thanks to our employees.”

Within the mill itself, the milling process takes up six stories, with each floor operating a very specific task turning wheat into flour. From sifting and separating to grinding and purifying, the mills churn out millions of pounds of flour a day. Bulk silos, visible from Hiawatha Ave., are used when necessary to store a few days’ worth of flour before it moves on to its new home.

Hatch says even the gluten free trend hasn’t impacted their flour sales, in fact, they’re still seeing growth.

“We’ve survived here in Minneapolis and we’re meeting the vital needs of the area and region,” said Hatch, “It’s great to be a part of that history and still be operating in Minneapolis.”

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here